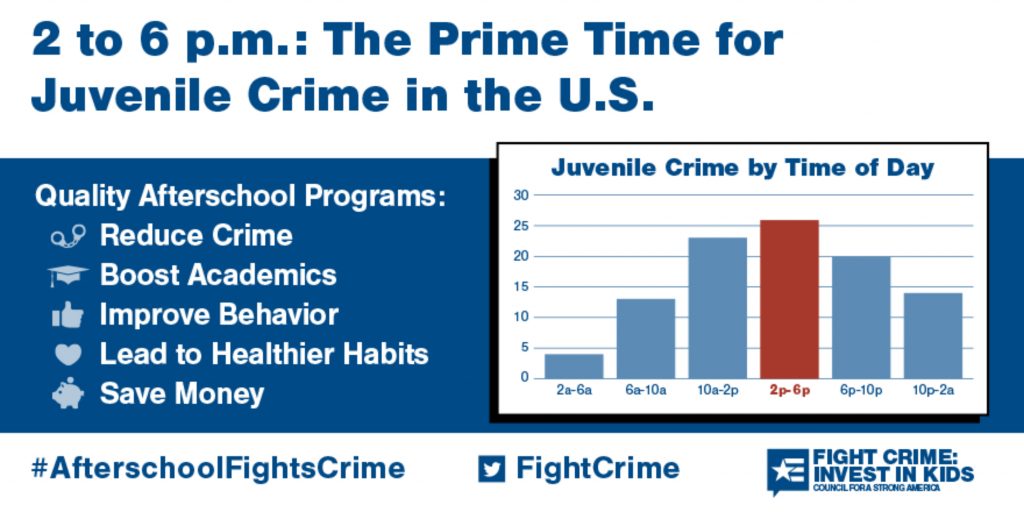

For decades, law enforcement has known that the hours immediately after school, when parents are less likely to be available to provide supervision, are the times when kids are more likely to commit or be victims of crime or to engage in risky behaviors. Last year, a report released by Fight Crime: Invest in Kids analyzed law enforcement agency and FBI crime data and was able to verify what law enforcement already knew: the time between 2 p.m. and 6 p.m. during the school week is the peak time for juvenile crime.1 Providing supportive, engaging, and enriching environments with caring, trusted adults can not only keep kids safe but can also keep them out of trouble and improve their academic outcomes, as well as their social and emotional development.

The Prime Time for Juvenile Crime

The good news is that juvenile arrest rates in the United States have decreased by 70 percent since their record high in 1996.2 However, juvenile crime continues to peak in the after-school hours. According to the most recent data available (2016), 26 percent of juvenile crimes occur between 2 p.m. and 6 p.m.; frequent offenses include assault, theft, and drug-related crimes.3

Across the United States, on any given school day, there are over 11 million children who leave school for an environment unsupervised by an adult.4 While the lack of adult supervision can clearly play a role in the increase in juvenile crime, so does boredom. A 2003 survey of teens and parents found that bored teens reported making poorer choices. They were also 50 percent more likely than not-often-bored teens to engage in risky behavior, make poor choices, and use illegal substances.5

Across the United States, on any given school day, there are over 11 million children who leave school for an environment unsupervised by an adult.4 While the lack of adult supervision can clearly play a role in the increase in juvenile crime, so does boredom. A 2003 survey of teens and parents found that bored teens reported making poorer choices. They were also 50 percent more likely than not-often-bored teens to engage in risky behavior, make poor choices, and use illegal substances.5

According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), youth are more likely to engage in violent crime on school days. In 2016, despite there being a near-even split between school days and non-school days in a calendar year, 62 percent of violent crime by youth occurred on school days, and of those crimes, most took place after school.6 This suggests that juvenile crime can be reduced through the use of quality after-school programming to keep kids engaged after the school bell rings.

Benefits of After-School Programs

Why do after-school programs reduce youth crime? These programs continue the supervision of teens after the school day, during the time of day when youth are most likely to be otherwise unsupervised, with mentoring, tutoring, academic, and athletic programming that are led by caring, trusted adults. However, these programs must reflect the needs of the youth and the community to continue keeping them engaged and returning to the programs.

The most effective after-school programs are sequenced, active, focused, and explicit (SAFE). This means that the program provides connected and coordinated sets of activities, active learning for students to learn new skills or attitudes, and targets and develops personal and social skills.7 Examples of a SAFE program include cross-age mentoring, learning cooperation and teamwork through team sports or games, guiding STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) skill development, and prompting the use of conflict-resolution skills.

Studies of structured after-school programs show that they can not only have an impact on juvenile crime but can also lead to improved academics and behavior, healthier habits, and cost savings.

Reduced Crime: Youth Guidance’s Becoming a Man (BAM), launched in Chicago, Illinois, in 2001, engages at-risk teenage boys to counsel them on life skills and problem-solving in high-stakes situations. A team of researchers at the University of Chicago studied the program during the 2009–2010 academic year and again between 2013 and 2015, and found a 28–35 percent reduction of total arrests and a 45–50 percent reduction in violent crime by participating youth. The same study also found a 21 percent reduction in recidivism.8

Higher Academic Achievement: A 2010 meta-analysis published of 68 after-school programs across the United States found that participants did better on state reading and math achievement tests, achieved higher GPAs, and had higher school attendance.9 Additionally, the above-mentioned study of the BAM program also reported a 19 percent increase in graduation rates among participants.

Improved Behavior: Studies have also found that after-school programs can improve students’ social and emotional skills. An evaluation of Wisconsin’s 21st Century Community Learning Center (CCLC) program found that participating students demonstrated improved school behavior, including being more attentive in class, having better attendance, coming to school more motivated to learn, and getting along better with others. The 21st Century Community Learning Centers Program is the only federal initiative that is exclusively dedicated to local after-school, before-school, and summer learning programs.10

Less Risky Choices: Youth who consistently attend after-school programs are less likely than their non-attending peers to engage in socially risky choices, such as using illegal substances—including marijuana and alcohol.11 In addition, parents of children in after-school programs say these programs can help reduce suicide risk, drug use, and teen pregnancy.12

Financial Savings: Juvenile crime carries a significant cost as well as an increased burden on law enforcement and youth services. The average cost of incarcerating a juvenile in the United States is $112,555 per year, almost five times the average tuition and fees paid by an out-of-state student to attend a four-year public university.13 By investing in quality after-school programs, society can save up to three dollars for every dollar invested through reducing crime and increasing children’s potential earnings.14

Law Enforcement‘s Role in Effective After-School Programs

Law enforcement has known for years that after-school programs are important tools in preventing juvenile crime and violence. Police athletic/activities league (PAL) chapters began over 70 years ago. Now 300 PAL chapters have built partnerships with their local law enforcement agencies. These programs create mentorship, civic, athletic, recreational, enrichment, and educational opportunities and resources for youth in their communities. They also create opportunities for law enforcement to build trust between law enforcement officers and the youth they serve, bonds that are more important than ever. Law enforcement agencies are engaging with after-school programs beyond PAL programs as well.

Detroit, Michigan: Police Athletic League

The Detroit Police Athletic League (PAL) brings after-school and summer programs to more than 14,000 children in the city each year. The programs primarily consist of large athletic and leadership programs to develop character and involve parents in supporting their children’s successes. These programs strive to invest in young people’s self-esteem, while getting youth to stay active and helping them to be successful in school.

The Detroit Police Department provides officers on a daily basis for PAL programs. Detroit Police Deputy Chief Todd Bettison, the liaison between the Detroit Police Department and Detroit PAL, says that he sees the effects of these programs: more young people staying in school, improving their grades, and having more hope and direction. In addition, the daily engagement helps to bridge the gap between law enforcement and the community.15

Burlington, Iowa: Partners in Education, Community Educating Students (PIECES)

Partners in Education, Community Educating Students (PIECES) after-school program in Iowa, provides Burlington Community School District students in kindergarten through 8th grade with a safe place to engage in learning activities in topics ranging from STEM to art.

Through the partnerships between PIECES and the Burlington Police Department, students receive mentoring from detectives in a crime scene investigation club and hear from female officers about being a woman in the field of law enforcement.

Recently retired Burlington Police Department Major Darren Grimshaw, who has been a volunteer with PIECES, said,

Afterschool programs give kids a safe place to be and a place where we can reach out and begin to break down some of those barriers that exist between the department and the neighborhoods.16

Knoxville, Tennessee: Boys & Girls Club of Tennessee Valley

The Boys & Girls Club of Tennessee Valley serves 1,400 youths daily and 9,800 youths and teens annually in the greater Knoxville area. Three-quarters of those kids come from nontraditional households (for example, single parent households). The program—funded partly by local, state, and federal grants—operates 17 sites that provide nutritious, healthy meals and academic and athletic opportunities.

Some of the program’s volunteers come from the great relationship the Boys & Girls Club has with the local law enforcement departments. In the past, several local agencies required their cadets to volunteer with the program in plain clothes (and not identify themselves as future officers). After they were sworn in, the officers would come back to the program sites in uniform. This type of approach builds empathy in police officers for the community they will be serving while also humanizing the officers in the youths’ eyes.17

San Mateo, California: Police Activities League

The San Mateo Police Activities League (PAL) program serves nearly 2,000 youths ages 5 to 18 in San Mateo, offering a variety of programs after school, including cooking classes, dance, interactive science, martial arts, sports, and leadership programs. The program focuses on building bonds between law enforcement and youth, providing juvenile diversion, developing positive life skills, and encouraging healthy, active living.

Retired San Mateo Police Chief Susan Manheimer, said of the program,

By partnering with our local schools and allied agencies, we’ve been able to craft comprehensive strategies that keep our kids in school, on track, and out of the juvenile justice system. Our officers develop relationships with high-risk youth when involved in these programs and also work with the schools and others for pre-arrest diversion and pro-social programs.18

Millions of Youth Are Still Left Out After School

While the programs listed in this article are noteworthy and successful in providing alternatives to the risks youth face during unsupervised after-school hours, they require resources, funding, and a commitment to youth programming. State and federal policymakers have heard the message from law enforcement that after-school programs are critical in reducing juvenile crime among our most at-risk youth. Since an initial report by Fight Crime: Invest in Kids in 2000 that analyzed juvenile crime data and found that the hours after school are the peak time for juvenile crime, funding and access to after-school programs have increased. Since 2004, participation in after-school programs has increased from 6.5 million children to 10.2 million enrolled in 2014, thanks, in part, to increased federal, state, and local investments.19

Even with this increased investment, millions of U.S. youth still do not have access to after-school programs. According to the Afterschool Alliance, for every single participant in a quality after-school program, there are two more who would participate but cannot because programs are unavailable to them. Research shows that there are more than 19 million youths (half are from low-income families) whose parents would enroll them if an afterschool program were available.20

How Law Enforcement Can Impact the After-School Hours

Build Partnerships with After-School Programs

As highlighted in the previous examples of the Greater Tennessee Valley Boys & Girls Club and PIECES, law enforcement agencies can partner with other community organizations––including local Boys & Girls Clubs, YMCAs, allied agencies, and school districts––to find opportunities for police staff to interact and build trust with local youth.

Apply for Funding to Bring Quality After-School Programs to the Community

In addition, law enforcement agencies can explore available funding to create and expand after-school programs in their communities. In the United States, there are several opportunities at the federal level, and often at the state and local level, to find funding to increase access for at-risk youth. Federally, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) provides grants for juvenile diversion and mentoring programs from which law enforcement agencies and their community partners can apply for funding. Funding from the 21st Century Community Learning Centers flows down to state education agencies based on its share of Title I funding for low-income students. These grants go to local school- and community-based organizations that serve students attending high-poverty, low-performing schools. There are also many funds at the regional and local level, particularly when collaborating with youth-serving agencies and nonprofits.

Advocating for Access for More At-Risk Youth

Finally, law enforcement leaders have a powerful voice—one that lawmakers trust when addressing juvenile crime. This is the premise of organizations like Fight Crime: Invest in Kids who enlist the power and influence of law enforcement leaders who can speak to law enforcement’s firsthand experience with at-risk youth. Advocating for increased funding for quality after-school programs will help ensure fewer at-risk youth are left unsupervised when they are most likely to commit a crime, be victimized, or engage in risky behavior. Oftentimes, these behaviors are the first “calls for help” on that slippery slope that leads youth into the juvenile justice system. The importance of keeping youth out of trouble early is borne out by compelling evidence that, once involved in the juvenile justice system, youth become much more likely to become adult offenders. Early intervention with youth prior to becoming involved in the juvenile justice system has a direct impact in reducing their recidivism and the crime rate. In turn, it reduces the burdens and costs incurred by communities and those that serve youth, including local law enforcement agencies. In the end, investing in youth crime prevention and youth development is an important investment in communities and the future. d

Notes:

1 Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, From Risk to Opportunity: Afterschool Programs Keep Kids Safe (Council for a Strong America, 2019).

2 Charles Puzzanchera, “Juvenile Arrests, 2017,” Juvenile Justice Statistics, National Report Series Bulletin (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2019).

3 Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, From Risk to Opportunity.

4 Afterschool Alliance, America After 3pm: Afterschool Programs in Demand (Afterschool Alliance, 2014).

5 The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University, National Survey of American Attitudes on Substance Abuse VIII: Teens and Parents (New York, NY: CASA at Columbia University, 2003).

6 Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention “Offending by Juveniles,” Statistical Briefing Book, October 2018.

7 Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, From Risk to Opportunity.

8 Sara B. Heller et al., “Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Field Experiments to Reduce Crime and Dropout in Chicago” (working paper, NBER Working Paper Series, no. 21178, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, revised 2016).

9 Joseph A. Durlak, Roger P. Weissberg, and Molly Pachan, “A Meta-Analysis of After-School Programs That Seek to Promote Personal and Social Skills in Children and Adolescents,” American Journal of Community Psychology 45, no. 3–4 (June 2010):285–293.

10 Tony Evers, 21st Century Community Learning Centers: Executive Summary, 2013–2014, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, September 2015).

11 Gabriel M. Garcia, Lori Price, and Neelout Tabatabai, Anchorage Youth Risk Behavioral Survey Results: 2003–2013 Trends and Correlation Analysis of Selected Risk Behaviors, Bullying, Mental Health Conditions, and Protective Factors (Anchorage, AK: University of Alaska Anchorage Department of Health Sciences, 2014).

12 Afterschool Alliance, America After 3pm.

13 Elena Holodny, “Juvenile Incarceration Is Way More Expensive Than Tuition at a Private University,” Business Insider, February 24, 2016.

14 William O. Brown et al., The Costs and Benefits of After School Programs: The Estimated Effects of the After School Education and Safety Program Act of 2002 (The Rose Institute, 2002).

15 Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, From Risk to Opportunity.

16 Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, From Risk to Opportunity, 11.

17 Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, From Risk to Opportunity.

18 Susan Manheimer (chief, Oakland Police Department, California; chief (ret.), San Mateo Police Department, California), email, March 31, 2020.

19 Afterschool Alliance, America After 3pm.

20 Afterschool Alliance, America After 3pm.

Please Cite as

Susan Manheimer and Joshua Spaulding, “After School: The Prime Time for Juvenile Crime—Partnering with After-School Programs to Reduce Crime, Victimization, and Risky Behaviors Among Youth,” Police Chief Online, August 5, 2020.