Since California legalized recreational cannabis in January 2018, pot enthusiasts in posh sections of Los Angeles can sleep easily with a few drops of CBD oil under the tongue. They can stroll into dispensaries such as MedMen, the chain touted as the “Apple store of weed,” which recently reported quarterly revenues of $20 million. On Venice Boulevard, shiny sedans toting surfboards drive past posters for Dosist vape pens and billboards for delivery services such as Eaze, a San Francisco-based startup that has raised some $52 million in venture capital.

In places like this, weed is chic. But just a few freeway exits away, in largely black and Latino neighborhoods where cannabis was aggressively policed for decades, people saddled with criminal convictions for possessing or selling the plant still fight to clear criminal records standing in the way of basic necessities: employment, a rental apartment, or a loan. Marijuana legalization and the businesses that profit from it are accelerating faster than efforts to expunge criminal records, and help those affected by them participate in the so-called “Green Boom.” And the legal cannabis industry is in danger of becoming one more chapter in a long American tradition of disenfranchising people of color.

From reading breathless media reports, it’s easy to believe we’re on the brink of a golden age for legal cannabis. Over the past year, investor enthusiasm for cannabis stocks has helped the legal marijuana market outperform Bitcoin and gold; in June, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first drug based on compounds found in marijuana; and a recent Pew Research survey shows that public support of legalization has doubled since 2000. Consumers in Los Angeles, currently the country’s largest market for legal recreational cannabis, can order it as pre-rolled joints, starter plants for home hobbyists, and fruit-flavored ganja gummies—all for delivery to their doorsteps. New York appears poised to legalize it within months.

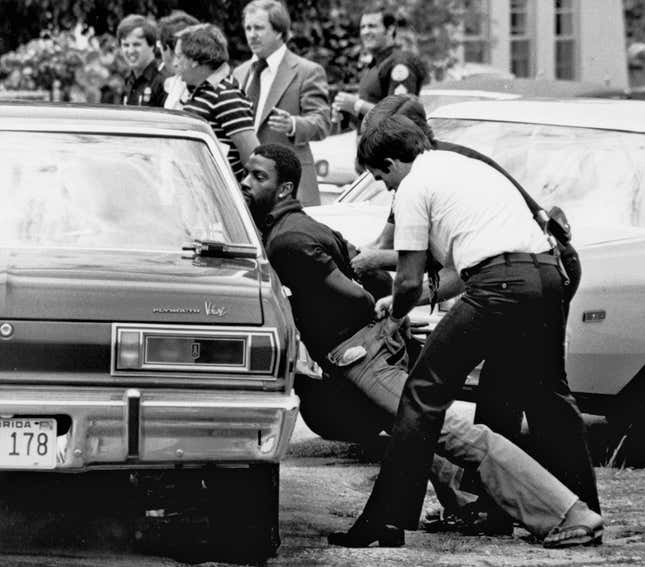

And yet, the Green Boom is leaving many Americans behind: in particular, those with cannabis convictions on their records. Many state regulations, as well as a new federal one in the 2018 Farm Bill, ban people with drug-related felony convictions from working in the cannabis industry. Those affected by these bans are are statistically much more likely to be black, because of systemic biases built into the criminal justice system. (Indeed, government officials who helped craft the enforcement tactics of the “War on Drugs” starting in the 1960s have admitted the policy was specifically designed to undermine black communities and fragment the political left.)

As the US teeters at the tipping point for marijuana going mainstream, it’s increasingly apparent that people and communities who were disproportionately punished for its criminalization were wronged. It’s a cruel footnote to the story of the plant’s legalization that punishment for past involvement with cannabis can remain a bar to entry in the lucrative newly legal industry. Now, policy-makers, entrepreneurs, activists, and everyday consumers are asking what reparations for those wrongs might look like.

Here’s one idea that many agree on: Those disproportionately affected by the War on Drugs—largely, black and Latino communities—should be first in line to benefit from the Green Boom, whether as business owners or beneficiaries of programs funded by earnings from the business.

The US’s legal weed explosion is an incredible story of de-stigmatization, entrepreneurship, and opportunity. It’s also at risk of becoming a staggering tale of hypocrisy, greed, and erasure. But as a deep-pocketed industry with political momentum, American cannabis is uniquely positioned to serve as a model for what racial reparations could look like.

“This is about harnessing the industry to embody the work of repair,” said Adam Vine, the founder of Cage Free Cannabis, an organization that pushes for “drug war reparations” in the form of criminal record expungement, job fairs, voter registration, health care, and social equity programs.

“Otherwise,” he said. “Legalization is just theft.”

How we got here: the War on Drugs

In his seminal 2014 piece for the Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations,” Ta-Nehisi Coates drew an unbroken line from slavery and Jim Crow to redlining—racial discrimination in real estate that segregated cities and left residents of black neighborhoods ineligible for loans. Redlining cut many black Americans out of home ownership, the country’s primary method for accruing generational wealth, and it created the conditions for segregated, poverty-stricken schools.

Three years after the practice was officially outlawed in 1968, those black neighborhoods became the primary targets for the US War on Drugs—a program of drug enforcement and mandatory prison sentencing that drove the mass incarceration that Coates and others have described as the next stage of the institutionalized racism central to US policy throughout the country’s history.

Coates continued tracing the thread in a devastating account of how mass incarceration continues that legacy today. “By 2000, more than 1 million black children had a father in jail or prison—and roughly half of those fathers were living in the same household as their kids when they were locked up,” he wrote. “Paternal incarceration is associated with behavior problems and delinquency, especially among boys.”

Established by US president Richard Nixon in 1971, and carried on by president Ronald Reagan with the help of his wife Nancy’s “Just Say No” campaign, the federal initiative demonized drugs, including marijuana, and those who used them, and has given the US the world’s highest incarceration rate. Between 1980 and 1989, the arrest rate for drug possession and use nearly doubled. And although surveys show that whites use drugs as much or more than blacks in the US, black people were arrested for drug-related offenses at five times the rate of whites in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In 1994, John Ehrlichman, the former domestic advisor to US president Richard Nixon dispelled any doubt that racism was at the root of the War on Drugs.

“You want to know what this was really all about?” he asked reporter Dan Baum, who was reporting a book about drug prohibition. “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Nixon’s team was continuing the work of Harry J. Anslinger, who took the helm of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics in 1930 and stayed there for more than 30 years. In 1937 Anslinger set the stage for decades of marijuana policy with the Marijuana Tax Act, which criminalized possession and was blamed for overcrowding at US prisons just a year after its implementation. Anslinger fanned the fear-mongering flames of “Reefer Madness” with sensational magazine articles, and left little doubt about his racial biases.

“In public appearances and radio broadcasts Anslinger asserted that the use of this ‘evil weed’ led to killings, sex crimes, and insanity,” reported Eric Schlosser in the Atlantic, adding that at different historic moments, he also linked the “evil weed” to the Japanese and communists.

That war is far from over.

In 2017, the drug-related arrest rate for blacks was still more than double that of whites, and a study by the National Registry of Exonerations found that blacks were five times as likely as whites to go to prison for drug possession. In some big cities, the statistics are even worse. In 2018, blacks and Latinos accounted for nearly 90% of arrests for smoking cannabis in New York City.

In 2018 the federal government’s budget (pdf) for drug control was just shy of $28 billion, and FBI data shows that the previous year, of nearly 1.1 million drug-related arrests, more than 40% were for cannabis-related charges, the vast majority for possession (as opposed to sale or manufacture).

“Evil weed” turned legal weed—and profit center

Meanwhile, the movement to legalize manufacturing and sale of cannabis is snowballing. In the late 1990s, just five US states and Washington, DC passed medical marijuana laws, followed by eight more states the following decade. As of the 2018 midterms, all but four allowed protections for cannabis use in some form, and New York is likely to join the 11 that allow recreational use.

Today, lawmakers such as New Jersey Senator Cory Booker are working to tie legalization efforts to expungement—giving people convicted of crimes such as the cultivation, possession, and sale of cannabis the opportunity to reduce their convictions and scrub records that can hamper access to housing, employment, citizenship, and the ability to vote. Those sorts of restorative measures, efforts to heal the wounds of the War on Drugs, largely haven’t happened as rapidly as legalization, meaning that while legal cannabis—now worth a whopping $9.7 billion in the US—has taken off, those punished for using and selling it pre-legalization have been left behind as criminals.

And some lawmakers today seem intent upon preserving the legacy of the War on Drugs. States including Nevada, Colorado, and Alaska restrict business licenses for people who have been convicted of drug-related felonies. On a federal level, the 2018 Farm Bill established hemp (defined as cannabis plants with less than 0.3% THC) as an agricultural commodity and removed it from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. But it also includes a provision that bans people with drug-related felonies from producing hemp for a decade following their convictions. (People with non-drug related felonies, however, are allowed.)

The so-called felon ban, which was a controversial late addition to the bill, is just one example of how criminal punishment continues to be used as a political tool when it comes to cannabis.

Hemp industry players and lawmakers alike spoke about their distaste for the ban, which some claim was added to appease conservatives such as Iowa Republican senator Chuck Grassley, who would have otherwise opposed hemp’s inclusion in the Farm Bill. But they accepted the provision as the price of doing business.

“I think it’s an unnecessary provision,” Smoke Wallin, the president of Vertical, a company that produces cannabis in Arizona, California, and Ohio, and hemp in Kentucky told me in November. “But it’s not a deal breaker.”

Given these measures, it should come as no surprise that white Americans are reaping the rewards of the legal cannabis boom. No statistical agencies comprehensively track the racial backgrounds of cannabis business owners, but in 2017, Marijuana Business Daily surveyed 389 cannabis businesses and estimated that only around four percent had a black person with an ownership—though not necessarily controlling—stake.

This has to change, said Vincent M. Southerland, a former public defender and NAACP lawyer who runs a think-tank on racial bias, inequality, and the law at New York University. But for the burgeoning legal cannabis industry to check its privilege and become more diverse requires a shift in mindset, and a reframing of the conversation.

“There’s a feeling or a sentiment that I, industry person, didn’t do anything wrong,” Southerland explained. “‘I didn’t create these laws, I didn’t put anybody in jail, I’m just profiting off of everything now.’ I think that same sentiment is what you hear when people talk about, ‘I didn’t build this segregated community, I didn’t build all these segregated schools, I’m just—my kids are getting a better education because of them now because they’re in these wealthy school districts.’”

Ongoing repercussions

On a sunny Saturday morning last autumn, Michael Saavedra, a 49-year-old Mexican-American paralegal with buzzed black hair and a grey collared shirt, sat at a folding table in an Inglewood, California community center beneath a banner that read “College Prep Not Prison Prep.” Saavedra had spent the morning volunteering at a legal clinic for Los Angeles residents who needed help clearing their records of past convictions for a variety of nonviolent crimes—the sale and possession of cannabis among them.

Jose Luis Moreno, a 62-year-old plumber originally from Mexico, clutched a dog-eared manila envelope as he left the event. “Es mi file de inmigración,” Moreno said, and explained that his bid for citizenship had been complicated by a cannabis conviction from 1979, after he bought $5 worth at the behest of an undercover police officer in downtown Los Angeles.

Although adults can now legally buy far more than $5 worth of weed from licensed sellers in California, the consequences from convictions like Moreno’s linger on. His wife and four children are all US citizens, but Moreno is not, which means he cannot leave the US to see his extended family—including his 90-year-old mother, he said, voice breaking—in Mexico City without risking being barred from re-entry.

Saavedra was volunteering at the clinic because he too had experienced the cascading affects of a cannabis conviction. He said he was pulled over at age 19 in 1989 in Los Angeles, and police found less than an ounce of cannabis in his car’s glovebox. The felony conviction and two-year prison sentence that followed altered the course of his life.

“It just kind of changed my whole perspective,” Saavedra said. “It influenced me in a really heavy way, because when you’re a young man like that and you’re in prison with older men who—there are more violent crime-related felons and gang members and prison gang members. So as a youngster, you are easily influenced by that and can get caught up in that very quickly.”

It doesn’t end with the prison sentence, Saavedra said. “[That cannabis conviction] put me in a position where now I’m a felon,” he said. “Now I’m on parole. You know, it’s going to be hard to get a job. It’s going to be hard to get housing.”

In 1998, Saavedra said he was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to 21 years in prison, 15 of which he spent in solitary confinement. While studying in the prison’s law library, he learned that the 2014 passage of California’s Proposition 47 gave him the right to petition for his cannabis conviction to be reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor. He filed his own successful petition, he said, and is now working to help others do the same.

Proposition 64, the law that legalized recreational cannabis in California in January of 2018, cleared the way for companies like Dosist, Eaze, and MedMen, and home gardeners dabbling with fewer than six cannabis plants. It also gave people convicted of crimes such as the cultivation, possession, and sale of cannabis the opportunity to reduce their convictions and scrub records that can hamper access to housing, employment, citizenship, and the ability to vote—a process known as expungement. But the state didn’t reduce or cancel those criminal records automatically, or provide any plans for implementing expungement, until a bill was passed in August of 2018 giving the district attorney’s office until 2020 to review cases that were deemed eligible for expungement. (Lawmakers in New Jersey are working to tie legalization of cannabis to expungement.)

In the meantime, citizens are free to fend for themselves when it comes to petitioning to clear their records, but it’s a challenging process that can be difficult to navigate—especially for those working with limited English or access to legal services, or a fear of deportation. That’s why Saavedra and others are mobilizing at a grass-roots level, spending their Saturdays offering advice and services in school gyms and community centers to help people like Moreno clear their records.

What we talk about when we talk about reparations

The word “reparation” comes from “repair,” which goes back to the Latin reparare—literally, to “to prepare again.”

Historically, the idea of “reparations” has taken on political resonance, referring to the damages paid in the wake of war. After World War II, the Germans agreed to pay 3 billion Deutsche marks to Israel, and an additional 450 million to the World Jewish Congress. Japan—its coffers drained by an estimated 42%—agreed to pay $6.7 million to the International Red Cross. Nearly 40 years later, US president Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, and agreed to pay $20,000 each to more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent who were imprisoned in internment camps during the war.

In the US, discussions of reparations circle around a moral reckoning with the nation’s deep-rooted history of slavery. As Coates wrote in “The Case for Reparations,” the cause has been taken up by former slaves and slaveowners, Quakers, civil rights activists, and more recently, Detroit congressman John Conyers, but—despite all evidence of racism’s ravages—has failed to capture popular support.

The actor and New York gubernatorial candidate Cynthia Nixon caught backlash in May when she used the word “reparations” while campaigning against governor Andrew Cuomo in a Democratic primary. Nixon suggested that people from communities “harmed and devastated by marijuana arrests” should be first in line for business licenses in the $9 billion boom that’s following cannabis legalization across the US. “It’s a form of reparations,” she said.

The statement raised some eyebrows, given the word’s loaded history—but Nixon had a point, and she was far from the first to make it. After all, the War on Drugs decimated communities, families, and individuals in the merciless manner its name suggests.

Is it the fault of today’s well-funded, legal, and largely white cannabis entrepreneurs that the US criminal justice system spent decades punishing black offenders at wildly disproportionate rates? No. But just as white Americans prosper disproportionately from an economy built upon slavery, redlining, and other forms of institutionalized racism, the marijuana industry’s astronomical growth comes with an ugly history—and present reality—of racial oppression.

Now that cannabis is becoming more widely accepted, there’s a growing conversation among business owners, activists, politicians, and consumers about whether reparations are due to those communities that suffered most under its policing, and how they could be implemented.

Reparations at the government level

Reparations are not easy to design: Should the thousands of white-owned businesses making good on the legal cannabis boom be paying part of their profits to Americans of color, who for decades have suffered staggering discrimination for the possession, use, and sale of cannabis?

Sending a check to every low-level offender who has been punished for using or selling weed is impractical—and politically impossible. But in Los Angeles, Oakland, and cities across the country, efforts and programs are underway to help the communities that suffered most from America’s misguided drug war to benefit from its Green Boom. As governments rake in hundreds of millions of tax dollars from cannabis sales, they arguably owe those Americans who suffered under the War on Drugs’ decades of racist policy and policing a leg up in this industry. In cities such as Los Angeles and Oakland, policy-makers are developing social equity programs to do just that, by awarding business licenses to selected applicants and holding workshops to help people navigate the bureaucracy.

“You have a multibillion-dollar business that black people ran,” said Jadili Johnson, who said he had gone to jail more than a dozen times in his decade-plus in the underground cannabis business, during which he said he refined hash and transported cannabis-enhanced edibles and beverages. “We consistently keep the industry going by taking the risk, getting our pockets checked.”

Johnson was attending a workshop about the licensing protocols for legal businesses growing, processing, distributing, testing, and selling marijuana, put on by the city’s Department of Cannabis Regulation in the packed gymnasium of a south Los Angeles community center in August.

This particular round of licensing was open exclusively to people who met the requirements for the city’s social equity program. The program was designed (pdf) to prioritize “individuals and communities that were disproportionally harmed by cannabis prohibition.” In other words, people from with prior cannabis convictions, low incomes, or zip-codes in areas like Inglewood, Compton, and swaths of south Los Angeles—historically black communities where people became statistics during the War on Drugs. People like Johnson.

What they—and I—learned was that the work of social equity is exceedingly slow, and mired in red tape. After a solid 40 minutes of PowerPoint slides and government jargon, the man in the folding chair to my right dozed off. To my left, another took notes in his phone.

From the podium, Cat Packer, the city’s first head of cannabis regulation, implored her audience to stay engaged. A former community organizer who wore a pale grey suit, well-worn oxfords, and her hair in a close crop to her head, Packer has said the research in Michelle Alexander’s 2010 best-seller The New Jim Crow—which connects the War on Drugs to the US’s racist history and present reality of mass incarceration—helped inspire her professional path.

“We are asking the cannabis industry—and not only the cannabis industry, but cannabis policy makers—to repair the harms that have been caused to individuals and to community members by past cannabis enforcement,” Packer told me on the phone after the meeting.

“Now, I will admit that I do not think that what we’re doing fits in line with the term ‘reparations’ in a whole, because I don’t think that the industry or government agencies can ever fully repair the harm that was done,” she said. “But I think that what we can do is to try and acknowledge that harm, and to promote policies that address that harm.”

Critics of the social equity program say that lack of funding and delays in application processing may be hurting the very people it’s designed to help. “This is the first time that regulatory agencies, government agencies, are licensing and regulating commercial cannabis activity,” said Packer. “So it being precedent-setting, I think is challenging.”

The programs in Los Angeles and San Francisco—like Oakland’s before them—allow those eligible for social equity benefits to team up with “incubator” partners who don’t qualify for the program, in exchange for support in the form of free rent or other business assistance. So a partner could put up the capital—including a hefty $12,000 licensing fee—and the social equity applicant’s status could send their application to a smaller pile. (Oakland even has a matchmaking program.) Some say this arrangement gives way to predatory partnerships, while others say simply, that’s capitalism.

The programs have gotten off to a slow start, to be sure, with hundreds of applications for social equity licenses still pending in Los Angeles and San Francisco. But there have been a few signs of progress. In September, former California governor Jerry Brown signed legislation allotting $10 million of the state’s budget to support city’s social equity programs through licensing fee waivers, business loans, and technical assistance. And in November, the improbably named Alphonso T. Blunt Jr., a fourth-generation Oakland resident with a marijuana-related felony, opened the doors at Blunts + Moore, the city’s first dispensary under a social equity permit.

Advocating for reparations

Bridgett Davis, the founder of Big Momma’s Legacy, a four-year-old Inglewood-based company that produces cannabis-enhanced topical ointments geared toward senior consumers—“my golden girls,” she calls them—is eligible for Los Angeles’ social equity program, but decided not to apply. She was deterred by the $12,000 licensing fee, a sum that would require taking on a partner. Or, as she put it, “a straw buyer.”

“As a small artisan brand, I don’t see the benefit right now,” she said. Instead, she developed her elevator pitch and planned for her next steps—to license her formula and brand to a distributor that can help her with the manufacturing, testing, and delivery of her products, allowing her to focus on sales and marketing—over 12 weeks, as a participant in a business accelerator program through the Hood Incubator, an Oakland, CA-based nonprofit.

While policy-makers are tied up in red tape and bureaucracy, community-based organizations like the Hood Incubator take a grassroots approach to supporting entrepreneurs like Davis with classes, apprenticeships, networking opportunities, and policy advocacy.

“We need to get people from our community—black entrepreneurs, brown entrepreneurs—into positions of growing strong businesses that can be able to stand the test of time, that can either compete with those brands that will receive the investment, or get them to grow to become investment-ready themselves,” said Hood Incubator cofounder Lanese Martin.

“It used to be weed sold itself,” she said. “Now it’s about the brand … It’s the marketing, it’s the story, it’s the distribution. It’s a lot more sophisticated. So we need our people to get up to that level of sophistication. You could have the best weed—you know, fire, or whatever—and have it in a Ziploc bag. Or you can have okay weed, and have it in a pretty jar, and be a lot more successful. Things are changing. So we need to invest in our entrepreneurs to get them to have the foundation to be able to compete.”

With her cofounder, Ebele Ifedigbo, Martin described the challenges of reaching that point in an industry that’s highly regulated, tightly networked, and capital-intensive. And unlike other Bay Area business sectors, where a college dropout in a hoodie is viewed as admirably “disruptive,” they say cannabis can be an industry highly conscious of appearances.

“People will use that as a reason to keep you out of the industry,” said Ifedigbo. “If you don’t have the right ‘credentials’—despite the fact that a lot of people in our membership have been involved in the underground industry for decades, like literally decades, out of their life.”

Reparations at the corporate level

While the Hood Incubator is part of a national alliance of grassroots organizations calling for drug-war reparations, its cofounder says the key is building a more inclusive industry: “How can we form in a way where 50, 100 years from now, it’s not only going to be rich white people benefiting from this industry, but actually the whole society has an equal opportunity?” Ifedigbo asked. “There’s an opportunity for business owners now to be part of that vanguard.”

The San Francisco-based company Eaze is one of the companies trying to take that opportunity. A tech platform that connects customers, dispensaries, and delivery services—sort of like Seamless for weed—it’s a significant player in the field, having raised over $50 million in funding and hired around 150 employees between Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego.

Because Eaze connects customers, dispensaries, and delivery services, it is well-positioned to guide the conversation around conscious cannabis consumption. And indeed, in February of 2018, Eaze hired Jennifer Lujan, formerly the founder of a medical cannabis donation program called Weed for Good, to be its director of social impact. In April, it hosted a roundtable at its company’s lofty new Venice Beach offices, where a cohort of cannabis company founders listened as the Department of Cannabis Regulation’s Cat Packer exhorted them to take responsibility for righting the wrongs of the past.

On a phone call shortly afterward, Lujan talked about Eaze’s strategy for social responsibility, outlining a plan that encompassed categories like patient support and economic empowerment. The latter, she said, is where the company hopes to address racial inequities.

“We’re going beyond writing a check,” she said, “but more offering our entire suite of services.” Eaze partners with multiple organizations, and gives employees time off to volunteer, she said, meaning that the company’s lawyers have helped put on expungement clinics—helping people wade through the morass of paperwork necessary to clear a cannabis conviction—and marketing execs have served as mentors and lecturers at the Hood Incubator, teaching classes about return-on-investment and sharing Eaze’s marketing data. (That said, the company does write checks for these causes too. The legal clinic where I met Saavedra was partially sponsored by Eaze.)

Eaze also serves as a matchmaker and a megaphone for the many companies it works with. (Some 70 cannabis brands are represented on the platform.) When Lowell Herb Co., a manufacturer of pre-rolled joints of organically grown cannabis, wanted to provide jobs for people affected by nonviolent cannabis convictions, Lujan was ready with a list of organizations to help facilitate their efforts.

Those efforts have fairly well-publicized, thanks to a billboard Lowell displayed off the freeway in downtown Los Angeles not far from two of the city’s major jails. “Recently pardoned?” it read, referring to people who cleared their record of marijuana-related convictions after California lawmakers passed Prop 64. “We’re hiring.”

“I’m a marketing guy,” the company’s CEO and co-founder, David Elias, told me. “I started my career in 1999…I’ve never seen a company really engage in making this a topic that people should really think about—what it means to have laws like this.” Beyond putting his company in the center of the conversation around cannabis and criminal justice, Elias said the billboard was a pretty effective job posting, bringing in over 100 resumes within 24 hours.

As was reported in the New Yorker, the company’s first hire through the effort was a former nursing student who lost her scholarship when the campus police found some weed and a pipe inside her purse in 2010. She now works for Lowell’s social media team, doing in-store demonstrations and developing partnerships with Instagram influencers and likeminded brands.

Elias said he sees his young company as a place to provide ex-offenders a second chance while the judicial system struggles to catch up with legalization. As Lowell experiences explosive growth—it launched in January of 2017 with five employees and currently has about 150, sells products in more than 300 stores, and joined MedMen’s investment portfolio in July—Elias said that means prioritizing more qualified job applicants who have been set back by nonviolent cannabis convictions, who he plans to reach through events like expungement clinics.

So far that’s translated to two full-time hires, and a company representative said the goal is to continue to hire someone affected by a nonviolent cannabis conviction quarterly. Two out of 150 seems a drop in the bucket, to be sure. But it’s a start.

Conscious cannabis consumers

So what is a morally concerned user to do? It’s a thorny question, but the worst answer, probably, is nothing.

For cannabis consumers eager to take an ethical stance, there’s a well-trodden path to follow in the rise of conscious consumerism in the retail industry and in food and agriculture. Indeed, a 2014 Nielsen poll of some 60,000 people found that 55% of online shoppers would pay more for products they believed had a positive social or environmental impact.

The Hood Incubator’s Ifedigbo acknowledged that investing company funds or staffers’ time in equity programs might be costly in the short-term, but that it reflects the sort of long-term vision shoppers like to see: “Consumers want to support businesses that they feel have a social mission, that are doing more than just making money, or just pumping out weed.”

And of course, consumers can communicate their desire for this by asking what cannabis companies are doing to address the inequities inherent to their business: Are they sponsoring job fairs? Expungement clinics? Making efforts to hire from communities affected by racist policing? However awkward that may seem to broach at a dispensary, they’re not unreasonable questions to ask, just as it wouldn’t be outlandish to ask a grocer for free-range eggs, or fair-trade coffee.

Packer hopes the Los Angeles Department of Cannabis Regulation will make that sort of shopping easier with a program requiring licensed operators to share their corporate social responsibility plans for her department to review, score, and make public. Picture a luxury dispensary, complete with a Whole Foods-type scoring system for cannabis that grades companies on their commitment to communities.

Cage-Free Cannabis has already developed an emblem that would indicate some level of social commitment from cannabis companies. It was inspired by philanthropic and politically minded companies like Newman’s Own and Patagonia (the outdoor gear-maker has led an alliance of companies that donates 1% of sales for environmental restoration for decades, a program that could arguably be called ecological reparations).

Of course, conscious consumerism in itself is no replacement for political action. And it’s worth remembering that the War on Drugs continues in the US—cannabis is still criminalized in many states, and the Trump administration seems newly focused on reinvigorating the anti-marijuana propaganda.

Citizens can also use organizations like NORML and the Drug Policy Alliance to find easy ways to contact or support elected officials opposing, for example, harsh sentences for nonviolent drug offenses or supporting states’ rights to legalize cannabis.

“Having the industry own this problem, it could in some ways foster an attitude on the part of consumers that someone else is already taking care of that problem or that concern,” said Southerland, of NYU’s Center for Race, Inequality, and the Law. “Participating in the political process is really probably the most important thing that the everyday consumer can do to try to change that dynamic.”