Russia’s protracted war in Ukraine could create a variety of outcomes for China to exploit against the United States, Western officials have warned.

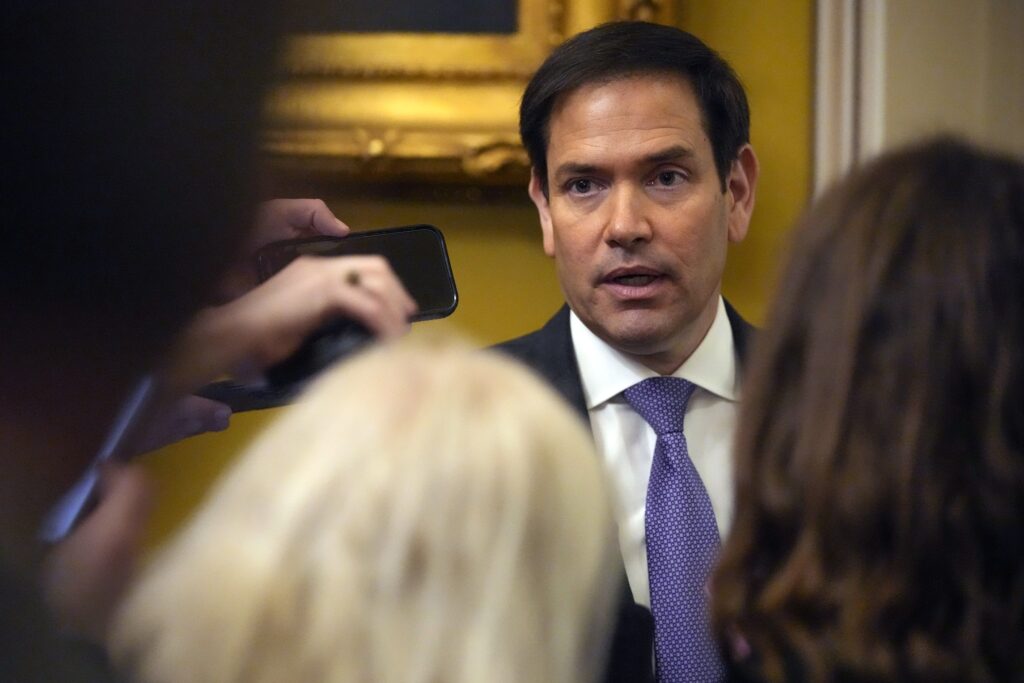

“The Chinese goal [with respect to Ukraine is], they either want us to deplete ourselves — spend all our time, money and attention on it — because they understand that every penny and every dollar we spend there is money that we can’t spend in the Indo-Pacific,” Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), a senior member of the foreign relations and intelligence committees, told the Washington Examiner.

“And on the flip side,” he continued, “if we don’t deplete ourselves, and we just abandon [Ukraine], then they’ll be able to go around the world and tell everyone — including Taiwan, and Japan and South Korea — ‘the Americans are unreliable, you can’t count on them.’”

That pair of possible futures has come into clearer view in the months since President Joe Biden ran out of funding authority to provide more weaponry for Ukraine, a lapse that has eased Russian efforts to bring more firepower to bear on the battered Ukrainian forces. Yet it also points to the complexities of the U.S. effort to develop a policy towards Ukraine that does not benefit China — a strategic dilemma exacerbated by the slow pace of Western efforts to increase the production of artillery and other armaments.

“A single European company, Rheinmetall [in] Germany, actually is producing way more 155[mm] artillery shells than the entire U.S. defense industry combined, as of now,” the Czech Defense Ministry’s Jan Jires said Wednesday.

That imbalance has a variety of causes, as the U.S. Air Force’s director for logistics acknowledged, ranging from corporate hesitation to expand production lines unless they are guaranteed “multi-year contracts” to a shortage of factory workers with the skill-set required to produce the weaponry.

“That skill set is older now,” Lt. Gen. Leonard Kosinski said during a Hudson Institute event with Jires. “A lot of them are almost leaving the workforce. How do we encourage young people to be able to take that on? That’s a very important job, and lucrative … These are things we’re working very hard on.”

Jires, the Czech director-general of defense policy and strategy, said that European defense production remains suppressed by an “even more frustrating” factor — a general sentiment, in the “ESG” wing of European banks, that there is something distasteful about investments in the European defense industry.

“In Europe, actually we have also faced a sort of culturally embedded unwillingness of banks and other financial institutions to invest in defense industry and to provide defense companies with financing either investment or loans,” Jires said. “Essentially, these banking executives believe that actually their shareholders and clients don’t want to see them putting money into defense industry.”

Those sentiments persisted for years after Russian President Vladimir Putin began the war in Ukraine, which erupted two years ago into the first major state-on-state conflict in Europe since the Second World War. And Russia’s larger defense industry, Rubio suggested, will necessitate that Ukraine agree to a ceasefire that leaves Russian forces in control of some occupied Ukrainian territory.

“The reality of it is that this conflict will end, or at least pause, when there’s a negotiation,” Rubio told the Washington Examiner. “There’s no way, I believe, that Russia will ever be able to achieve their initial goal, which was to take Kyiv and the entire country … it’s equally difficult for Ukraine to push back the Russians to where they were before 2014, simply because Russia is a bigger, larger country . . . these are realities, it’s not what I want to be the case. And, I think both parties acknowledge that, and, maybe not publicly, but the U.S., too.”

Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski argued, this week in Washington, that the United States has an existing arsenal of weapons adequate to the need this year in Ukraine — an assessment echoed by some American analysts.

“There’s weapons already sitting there,” the Hudson Institute senior fellow Rebeccah Heinrichs said on Wednesday. “Ukraine needs weapons now. And, we have them on the shelf to send to them. We just need to make sure that we’re replenishing our own stocks.”

Rubio emphasized that he would like “Ukraine to have more leverage than Russia” when those talks take place. Even so, that line of reasoning carries its own potential to damage U.S. relations with its most supportive allies in Europe.

“The U.S. will destroy its image in Europe,” a senior European official, who hails from a country that joined NATO after the collapse of the Soviet Union, told the Washington Examiner. “All the Central [and] Eastern Europeans — who are [rebuked] by the Western Europeans that ‘hey, you are more in union with the U.S. than in the European Union, actually’ — we will be deeply disappointed. Because that means that you will leave us with all the consequences.”

Jires and other officials are trying to ease the burden on the U.S. by identifying “a huge number of already existing” stockpiles of artillery rounds “in non-Western countries” which are unwilling to send them directly to Ukraine, but would be willing to sell them to Ukraine’s European backers.

“They need a middleman,” he said. “They need somebody actually to facilitate those supplies, so this is what we’ve been organizing … bringing that materiel to Ukraine as soon as possible.”

Across the eastern flank of NATO and Ukraine, officials agree that even a partial Russian victory in Ukraine would empower the Kremlin to start the countdown for another and more dangerous war.

“If we are not able to unite [our] efforts and do what we have to do, the consequences of this war will be larger,” Ukrainian deputy foreign minister Emine Dzhaparova said this week during a separate Atlantic Council event marking the tenth anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula. “There is a huge risk of global war in case the Ukrainian issue will not be solved, to this or that extent.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Rubio agreed, at least to a point. “Yes, I think if you reach a negotiated settlement, Putin would recalibrate and reposition himself and come back at it in three or four years; that’s a real risk,” he said. “The flip side of it is that it’s gotten harder and harder, every time, to get funding here — not because people hate Ukraine and love Putin, but because we have competing priorities … We have our own set of challenges, and every penny we’re spending is borrowed money. So there’s real concerns in that regard.”

If U.S. leaders can’t navigate that dilemma, China may take advantage in capitals far removed from the Indo-Pacific. “China will only applaud when the transatlantic ties will be damaged,” the senior European official said.