In the crosshairs: Chinese drones a target for US ban as security risk

- Shenzhen-based DJI, the global leader in drone technology, is confronted with several US efforts to prohibit the sale and use of its products

- In recent months, US lawmakers have introduced two dozen drone-related bills, many aimed at restricting Chinese drones and building up US industry

In February, police in Fremont, California, used a DJI Technology drone equipped with a thermal imaging camera to locate an emotionally troubled boy who had gone missing at night. After running away from school, the deaf teenager hid in a field where the drone found him, and helped return him to safety.

DJI, the drone manufacturer based in the south China city of Shenzhen, hopes stories like this one will blunt mounting suspicions, increasingly restrictive regulations and other collateral damage from the deteriorating US-China relationship that is threatening its business.

But increased turbulence for the world’s largest maker of commercial small drones seems inevitable. Sharing headlines with the heartwarming tales are cases of DJI drones involved in terrorism incidents, crashes on the White House grounds and prison drug deliveries.

And Washington, after long dismissing small drones as mere playthings and finding itself miles behind in an increasingly strategic industry, is marshalling protectionist legislation, subsidies and patriotic appeals hoping to make up for lost time.

“The global market was asleep at the wheel. The Chinese started out building these as toys,” said Christopher Williams, chief executive with San Diego-based Citadel Defence, which sells counter-drone technology to safeguard sensitive sites.

“The US is only just picking up on it.”

DJI unveils drone-to-phone tracking technology

In recent months, US lawmakers have introduced more than 20 drone-related bills, many aimed at regulating or restricting Chinese-made machines and building up US competitors.

Most prominent is the National Defence Authorisation Act (NDAA) that directs spending of the US$780 billion annual military budget, which has passed both houses and is expected to become law in coming weeks. Language contained in the 1,976-page bill would effectively ban the US military from buying Chinese-made drones.

Tougher still is the American Security Drone Act of 2019, which has been introduced in both houses but is several steps away from becoming law. This would halt federal, state and local government purchases of Chinese drones and set a retirement timetable for those currently in use.

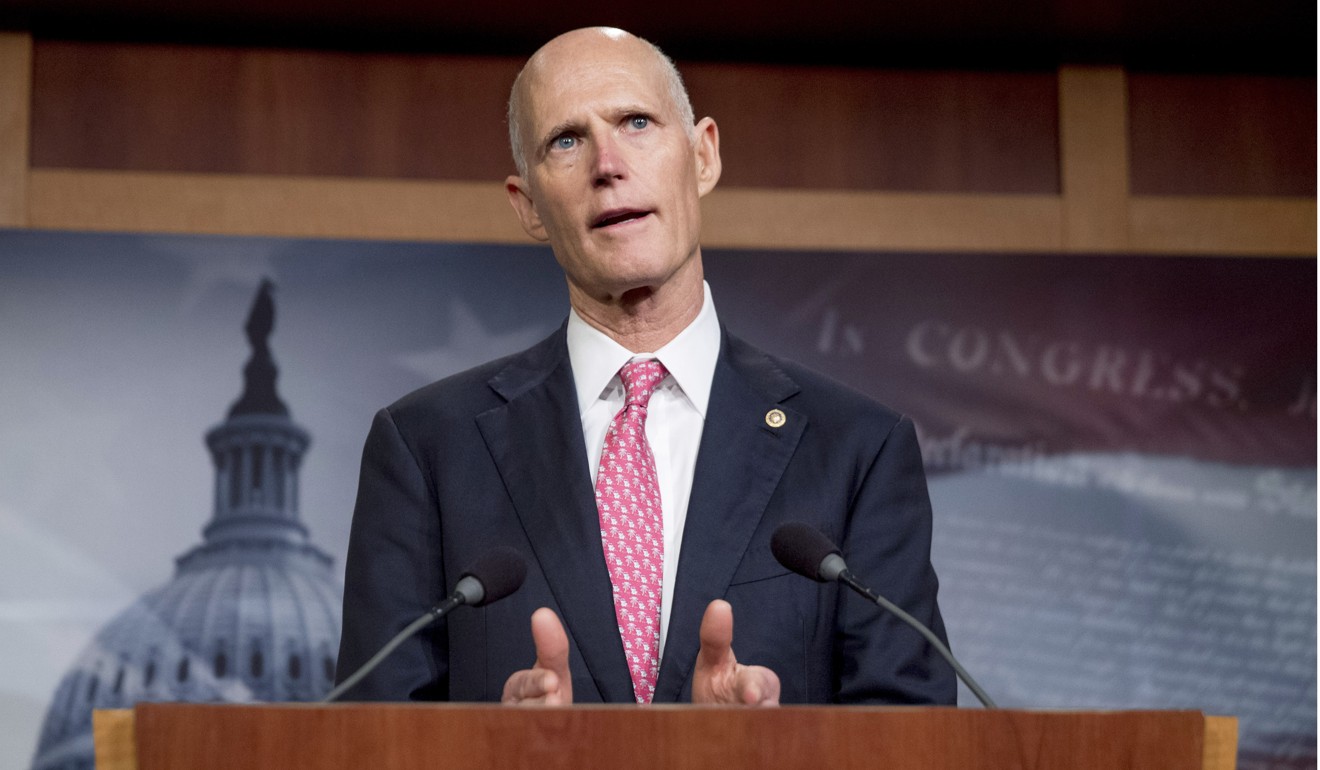

“We have to get serious about the national security threat we face from Communist China, who is stealing our technology and intellectual property,” said Senator Rick Scott, the Florida Republican who has sponsored the Senate version.

“The US government continues to buy critical technology, like drones, from Chinese companies backed by their Communist government. We cannot allow this.”

On other fronts, Washington has dusted off the Defence Production Act of 1950 originally used to spur aluminium and titanium production during the Korean war. After the White House designated drones a strategic industry in June, citing the risk of “domestic extinction”, the law authorises Washington to nurture US commercial drone makers.

The act’s tools include guaranteed federal contracts, preferential loans, antitrust exemptions, even venture capital – state actions from a Washington that has long criticised Beijing’s aggressive support for strategic industries.

The defence department also recently spearheaded a public-private partnership matching venture capitalists with nascent US drone makers. And it invited five US companies – all tiny by DJI standards – to compete in building a prototype small reconnaissance drone for the US Army with the lure of guaranteed government contracts.

“It should come as no surprise that industry leader DJI is not taking part in the innovation effort,” said DroneLife, a trade newsletter.

Privately held DJI does not release its financial results, but data firm Skylogic Research estimates it had about 74 per cent of the 2018 global commercial drone market. Others peg its US share at 80 per cent. The value of the global drone market, currently about US$4.9 billion, is expected to triple over the next decade.

DJI drones adopted by US agencies despite Trump’s concerns

Even without the new laws, DJI faces growing headwinds. In October, the US Department of the Interior halted all non-emergency DJI drone flights. Five months earlier, the Department of Homeland Security warned that Chinese commercial drones may be collecting and sending data back to Beijing. And last year, the Pentagon widened a 2017 US Army ban on the use of all DJI drones.

Most existing or proposed restrictions target government purchases – a relatively small part of DJI’s US business – although growing anti-China sentiment, tax and tariff proposals could hit its US commercial and consumer business.

As well as security concerns, DJI’s critics argue that it has not played fair. Building viable US commercial drones – also known as unmanned airborne systems, or UAS – would not be so difficult, they say, if DJI had not crushed US makers like GoPro and 3D Robotics in 2015 and 2016.

“We don’t have much of a small UAS industrial base because DJI dumped so many low-price quadcopters on the markets,” said Ellen Lord, the US defence undersecretary for acquisitions and sustainment.

“And we then became dependent on them, both from the defence point of view and the commercial point of view, and we know that a lot of the information is sent back to China from those. So it’s not something that we can use.”

DJI North America spokesman Michael Oldenburg said that Beijing had never asked for customer information “related to that specific security law. And it’s impossible to hand over information we don’t have.”

Users controlled the data generated aboard their drones, he said, adding that the NDAA and Security Drone Act had a misguided focus on a device’s country of origin rather than setting out transparent standards.

“There’s a concerted effort [throughout Washington] to specifically target Chinese technology companies. We’re obviously keeping an eye on it and the current administration is quite unpredictable,” Oldenburg said.

“Some in the US seem to have this fairy-tale idea that drone manufacturing is going to come back to the US. Technology manufacturing moved overseas a long time ago.”

China tests killer drones for street-to-street urban warfare

Few underestimate the challenges that US commercial drone makers face given DJI’s commanding lead and the growing appetite for its products in mapping, surveillance, safety, counterterrorism and package delivery, among other uses. The Federal Aviation Administration estimates that 7 million drones will be operating in US airspace by 2020 – nearly triple 2016 levels.

“The US is now in this position of realising ‘Wow these little flying robots are getting pretty damned sophisticated, and they can grab pretty sensitive data, and they’re all being made in China’,” said Colin Guinn, an industry veteran and head of technology consultancy Guinn Partners.

But the US has also made mistakes. Promising domestic competitors have stumbled. Drone-related legislation has often been patchwork. The technology has far outpaced lumbering regulators, including a 2007 FAA policy subjecting commercial drones to the same restrictions as aircraft, a move critics say squelched innovation.

“We were about 20 years ahead of the Chinese,” said Patrick Egan, Americas editor at sUAS News, a drone industry media group.

“We got out of the Camaro with the keys running, all gassed up and ready to go, and handed it to the Chinese.”

Others say the Pentagon’s focus on multimillion-dollar drones made by huge military contractors left it blind to the strategic value of small drones.

“The US engineering process is so bloated and slow, compared to what they can do in China with US$30,000 engineers who will work 90-hour weeks and work really fast,” Guinn said.

“By the time the US team finishes its first prototype, the Chinese will have made 14 prototypes and the last one looks almost ready to ship.”

That has left the Pentagon scrambling to reinvent the wheel, potentially settling for equipment that is a generation behind, in hopes of building a capable industry over the longer term.

“Today the US military is not able to buy a drone as capable as what you can buy in Best Buy for US$2,000,” said Spencer Gore, founder and chief executive of California-based drone maker Impossible Aerospace, who lobbied for the anti-Chinese language in the NDAA.

Gore sees a shortage of US foresight: “Now we’re spending up to US$100 million to bring these companies back to life. Is that the best use of taxpayer money, rather than not letting them die in the first place?”

The defence department did not respond to a request for comment. The FAA said it had evolved after realising early on the need to safely integrate drones into US airspace without stifling innovation.

“We recognised that we needed to be more flexible and nimble than we had been in the past,” spokesman Ian Gregor said, adding that “safety is our core mandate”.

Why BYD’s electric bus operations may be cut short in the US

Other Chinese companies, including the telecommunications giants Huawei Technologies and ZTE and the electric bus maker BYD, have reacted slowly at times to mounting US political pressures in a period of rising US-China tension. But DJI has generally responded promptly to criticism, ceded authority to an army of US lobbyists and publicists, and restructured its operation to address US concerns.

In Congressional testimony, DJI has touted a purported US$1 billion in economic activity and 82,000 potential US jobs from the US commercial drone industry, which it dominates, as well as opportunities for US companies that sell value-added services for drones it and others make. It has commissioned security audits and launched DJI Government Edition drones with extra safeguards, and has also taken a cue from past missteps.

“When we saw our older peers like ZTE or Huawei, saw some of the things happening to them, saw the entity list, we started paying a lot more attention because it started hitting home,” Oldenburg said, referring to Washington’s list of foreign companies that are blocked from buying strategic US technology.

“We’ve learned from other companies in positions we don’t want DJI to be in.”

But politically, DJI often finds itself flying solo. It lacks many vocal US advocates – even quietly supportive budget-pressed police forces wary of paying more for inferior US-made equipment – given the optics in the current climate of defending Chinese interests. Asked the relative utility of DJI drones, both the National Association of Police Organisations and the International Association of Chiefs of Police did not comment.

Tech marketer Guinn, meanwhile, disputes criticism that vertically integrated DJI has relied on massive state subsidies or predatory pricing. Guinn, then a Hollywood videographer, met and hit it off DJI’s founder, Wang Tao, in 2011, five years after Wang had established the company in his dorm room at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Following an unpromising start, DJI relocated to Shenzhen and focused on aerial video and photography equipment – which has since been used in a slew of film and television productions, including Better Call Saul and Game of Thrones.

How DJI went from dorm project to world’s biggest drone company

Soon after their meeting, Guinn established DJI’s North America operation before parting in 2013 over vision and ownership differences. After filing and settling a lawsuit on undisclosed terms, Guinn joined 3D Robotics’ ultimately unsuccessful bid to counter DJI’s might.

Wang’s big competitive fear was never fledgling US drone makers but behemoths like Sony, Apple and Samsung, Guinn said.

Wang’s response was to build market share with razor-thin profit margins – in part by arm-twisting retailers like B&H Camera and Best Buy to pay up front for inventory – resulting in pricing that discouraged the technology giants, Guinn said.

“All these companies looked at making a drone. It was not predatory but very shrewd, very aggressive strategy.”

Guinn said that despite past differences, he was still in touch with Wang, whom he described as a “nerdy engineer for sure, super nerdy”.

“You play to win,” he said. “But a lot of his action could be seen as totally ruthless because for him it’s just numbers, just engineering.”

For more insights into China tech, sign up for our tech newsletters, subscribe to our award-winning Inside China Tech podcast, and download the comprehensive 2019 China Internet Report. Also roam China Tech City, an award-winning interactive digital map at our sister site Abacus.