|

The tradition of maple sugaring runs deep in Vermont in the land and our people. From small sugarshacks tucked into backyard woods to larger more commercial operations that help make Vermont the number one producer of maple syrup in the country, sugaring remains a key part of our economy, identity, and heritage. Maple sugaring in Vermont is often a family-owned, multigenerational affair.

Vermont has led the U.S. in syrup production since 1916. And while we still led the nation last year, our state just saw one of the shortest sugaring seasons in over a decade. Studies have shown climate change and extreme weather events are threatening the industry, so we sat down with Emma Marvin of Butternut Mountain Farm in Morrisville, Vermont to hear her thoughts.

The Marvin family have been a major part of Vermont’s sugarmaking community for over 40 years. Their family-owned, multigenerational Butternut Mountain Farm is now one of the largest maple processors and distributors in the United States.

Here are some excerpts from the conversation.

(This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

Q: Hi Emma, thanks for sitting down with us. So, to start off, can you tell us a bit about Butternut Mountain Farm?

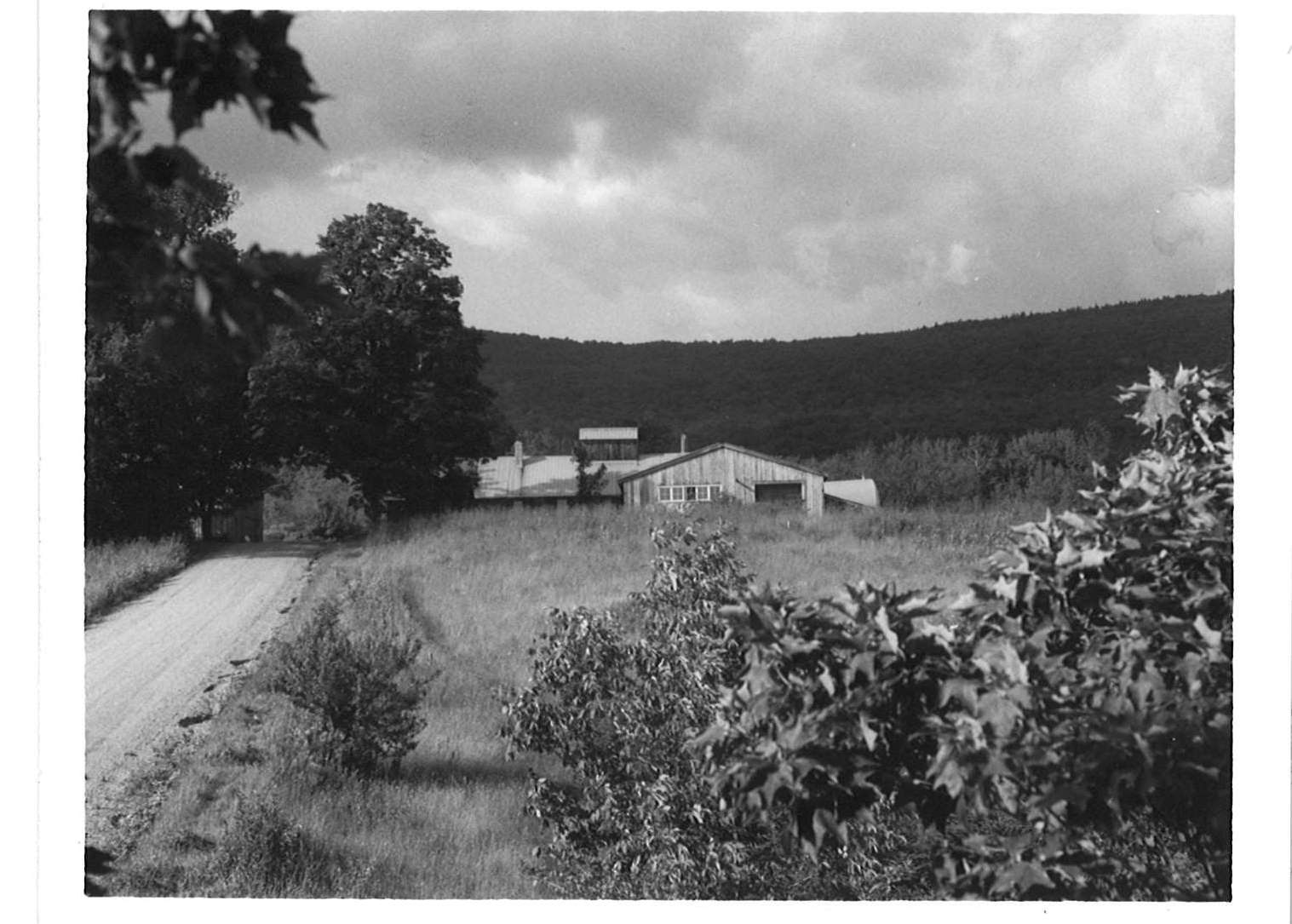

Emma: Our packaging plant is in Morrisville. We have just under 150 employees now, and we source from nearly 500 Vermont farms beyond our own. Our home farm is in Johnson, on the side of Butternut Mountain. My grandparents purchased the land that my father developed into our farm in the 1950s. My Dad started Butternut Mountain Farm in 1972, so we've been in the business for a while. My brother and I are the co-owners of Butternut Mountain Farm. We have completed the transition from first-generation to a second-generation ownership.

Q: Wow, that's great. I know succession in terms of family farming can be tough, so that’s great to hear. Can you speak a bit about what the farm means to you and your family?

Emma: For us, it's a way of life and it is how we make our living. I think all of the Marvins feel incredibly lucky to be of a scale that it can support our families and the families of the employees. We now have a Butternut Mountain Farm business that has grown in such a way that we can serve as an access point to markets that would otherwise be too large for any single producer of maple syrup here in Vermont to access. And we feel incredibly fortunate. Maple is something that is unique. I think all of us here in Vermont take a special pride in maple and most Vermonters are amazing ambassadors for maple syrup, so to be able to be connected to the industry and the land through this product is pretty special.

Q: And for the few Vermonters who may not be familiar with Butternut Mountain Farm, could you just describe that model? So, you're collecting and sourcing syrup from farms across the state and then packaging it, or do you make it into maple products to then distribute and sell?

Emma: All of the above! Today we provide maple syrup to major retailers across the U.S. and internationally, as well as to food manufacturers and food service distributors. For a lot of the smaller, local producers that choose to work with Butternut Mountain Farm, we are their market for the syrup they produce. And that really allows them to focus on making a top-quality product and on being good stewards of their woodlands. And we assure them that the product they make has a place to go year in and year out.

Q: You started out as a family business and you still are family owned. But you mentioned you have a pretty large workforce now. And what does that look like?

Emma: You know, for me, I grew up in this business. Our first employee, who's worked with us since before I was born, just retired this year. We've had an incredible group of employees over the years, some of whom have an incredibly long tenure with Butternut Mountain Farm. My hope is that the folks that come to work with us feel the way I do, that this is a great way to make a life and a living. I hope they also feel like they're treated the way we treat our family.

Q: Senator Sanders is concerned about climate change both as an existential threat and also because of how it threatens a lot of traditional Vermont industries, including maple. Can you speak to how the farm and the sugaring industry in Vermont has been impacted by climate change?

Emma: We just put up a blog post on this issue back in November, and I encourage everyone to take a look at that. I think maple is at a really interesting intersection as it relates to climate change. Because we both have the potential to be dramatically impacted by it, but we also potentially have a role to play in climate change mitigation, particularly as it relates to carbon sequestration. Maple is one of the few foods that is harvested from the forest. And research increasingly shows that the northern forest is one of the best carbon sinks in the world. So, there's this opportunity, I think, for maple to play a continued role in making sure that northern forest stays intact, because there's this economic value that the forest is generating year in and year out. And maple is so interesting in that we're leaving the carbon in the woods, you know, we only take a little bit of carbon out in the form of sugar each spring in the form of sap. And otherwise, all of that stored carbon stays intact in the forest. And there’s incentive to do that as maple sugar makers. Because the forest is where our living comes from.

Q: That makes a lot of sense.

Emma: I think we're all concerned about the potential impacts of climate change. Research suggests that over maybe say the last 60 years or so, sap collection is shifting earlier in the calendar year. We know that the frequency and severity of storm events are increasing. And when you have a harvest that comes from a long-lived plant, severe storm events that have the ability to impact the forest can be absolutely devastating. But on the flip side, the ecosystem services that that forest is providing are absolutely essential for also mitigating the impacts of those storm events.

Q: And is it true that the ideal conditions for sugaring are sunny days and cold nights? Are you experiencing any issues as temperature trends change?

Emma: Yes. Sap production is really dependent on a narrow window of temperature ranges. Typically, sap flows when daytime temperature is above freezing and nightfall is below freezing. So, it is very reasonable to be concerned about climate change impacting the maple harvest from that perspective. I think the maple industry largely has been really good at deploying technology to mitigate some of those risks – vacuum systems being one of them. And I think we'll continue to see technological advances to mitigate the impacts. But you really do need that change in temperature for the sap to flow.

Q: And if you could speak to members of Congress, Senator Sanders or otherwise, as a farmer and a small business owner, about the need to act on climate change, what would you say to them?

Emma: Oh, so much! It's hard to say succinctly. I think I said some of it already. Maple is in a unique position, both to help be part of the solution to climate change while also acutely feeling the impacts of climate change as it happens. I think figuring out how to make sure we keenly understand those relationships is really important.

Q: Have you already had to adapt to climate change at Butternut Mountain Farm, and if so, has it been difficult?

Emma: Every action we take at this point is an action we take with a recognition that it has an impact. I think the difficult part is wondering if we're doing enough. I think, particularly as it relates to our farm, we're constantly thinking about how to mitigate the risks associated with severe storm events. How do we make sure that we are not putting ourselves in more of a position of risk as it relates to species diversity and those kinds of things? As a business, we constantly try to evaluate what the impacts of our decisions are from a carbon perspective, and we're certainly nowhere near as advanced in that analysis as we'd like to be.

Q: And one last climate question. What do you think has to happen for more people to understand the urgency of the climate crisis? Should people be worried about climate change impacting the availability of maple syrup?

Emma: My hope is that Vermonters and folks across the U.S. come to think about maple as one of the few products that they can consume and feel good about the carbon footprint. That's the story I'd much rather people remember: that maple is an incredibly unique product in terms of its capacity to be carbon neutral or even better than carbon neutral. Maple can, in fact, encourage the sequestration of carbon because it comes from a long-lived plants that we're only taking a tiny bit of carbon from in the form of sugar and the rest of it stays in the forest, sequestering that carbon. So I think that's the story. I would really like people to keep in mind about maple and the recognitions that when folks begin to worry about whether there's going to be maple on their pancakes or maple from Vermont anymore, that the climate crisis is at a point where it's so dire that I expect it'll be the last thing we'll be talking about. There'll be mass migration of population at that point, and my hope is that we all are taking individual and collective actions to mitigate the potential path that we're on and redirect where we're heading.

Q: And lastly, you live and work in a pretty rural area. What do you think are the best parts of that rural life? What do you love most about it and what do you value?

Emma: All of it! It's such a treat to come home to Vermont after I travel. I think there's something incredibly special about the community here. I think the scale of Vermont is very human and very accessible. And that's on so many levels. It's those local gathering places. It's the community connections. It's the accessibility of government. It's the sense of both independence but also desire to make sure that our communities are vibrant and robust. So that makes Vermont really special. And I think a lot of people wonder why Vermont looks the way it does in terms of, for instance, COVID vaccination rates. And as I think about it, it's a lot about doing what's right for you as an individual, but also being willing to do what's right for your neighbors in your community. And I think Vermont has had that in a way that many places don't. And I also think the land here has shaped a lot of why our communities look the way they do, but the people have also shaped the landscape and how it works. It's really that synergy that creates this amazing place.

Q: Emma, thank you for sitting down with us and sharing your experience and expertise.

Emma: Thanks for reaching out. Really appreciate it. |